By now you may have heard that the Heritage Foundation purchased the former O’More College of Design campus, and that it is now known as Franklin Grove.

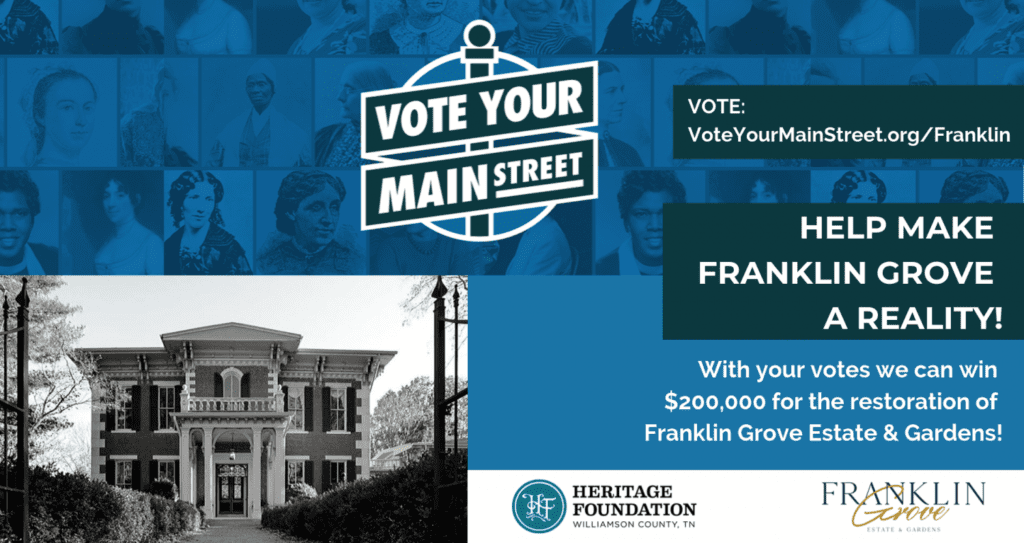

You may not know that Franklin Grove has been chosen as a finalist for a national grant sponsored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and American Express.

Partners in Preservation is a national effort to celebrate the contributions of women in their local communities, in honor of the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment given women the right to vote. This property’s history is a testament to those contributions.

Franklin Grove is a 5-acre sanctuary at the edge of historic downtown Franklin, hemmed in with a brick and wrought-iron fence that, for centuries, separated it from its neighbors in the 16-block business district.

The property had been mostly sequestered from the public for more than 200 years until February 2019, when the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County purchased it from Belmont University. The community feared the property would be sold for residential development because of its prime location within walking distance to downtown. So Heritage Foundation members rallied and within months had assembled the $6M required to buy the property with the goal of transforming it into a jewel the public could enjoy for decades to come.

Once they closed on the property, the Heritage Foundation, led by CEO Bari Beasley, began delving into its history to come up with a new name appropriate for its new vision as a destination for arts, preservation and education. For decades it had been known as the home of O’More College of Design, founded in 1967 by Mrs. Eloise Pitts O’More. After a successful career in interior design, O’More remembered that when she started out, there were no women architects, and interior design was thought of as “just decorating,” more of a hobby than a career. She wanted to change that.

O’More was continuing a tradition of female education on the property that extended back to the early 1800s, when newspapers advertised a “seminary for women at beautiful Franklin Grove.” The Hines family advertised in 1832 a seminary offering “Female Education including…Needle-work on Muslin, Canvas, Bolting…Tambour, Lace-work, Embroidery on Satin and Velvet, Drawing, Painting on Paper and Velvet [and] Music.”

The Rev. Canelm Hines and his wife Sarah began operating the school in 1832 and ran it until the Civil War came to Franklin. Just after the war, during Reconstruction, the Hines’ daughter Sallie Hines McNutt returned from Virginia to find a Freedmen’s Bureau school in her home, educating newly freed African Americans.

Upon discovering this history, the Heritage Foundation staff and board settled on the “new old” name Franklin Grove and are in the planning and design phase for the property.

You can help Franklin Grove win its share of $2M in grant funds toward the restoration of the property. Just go to https://www.nationalgeographic.com/voteyourmainstreet/franklin/

to vote. You can vote up to five times per day.

At the turn of the 20th century, Tennessee played a pivotal role in the passage of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote in 1920. By that summer, 35 of the 36 states necessary had ratified the amendment. Suffragists saw Tennessee as their last, best hope for ratification before the 1920 presidential election.

The most interesting detail of the 19th amendment’s ratification story in Tennessee is that a legislator’s mother seems to have had the most influence on the decision to vote in favor of ratification. Harry Burn, a 24-year-old legislator from East Tennessee, had cast the deciding vote in the contentious campaign after weeks of fierce lobbying on both sides. Until the final vote, Harry Burn had been strongly in the camp against ratification, at least until he received a note the morning of the final vote from his mother, which read in part, ““Dear Son, … Hurray and vote for Suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt. … I’ve been waiting to see how you stood but have not seen anything yet…. Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt with her “Rats.” …. With lots of love, Mama.”

Burn’s mother was the widow of a farmer and a strong influence in her son’s life. This mirrors the motivation of Eloise Pitts O’More, who created a school for design from a large tract with not one but two 19th-century homes. She left her small hometown of Lewisburg, Tennessee, to study in New York and Paris, and opened O’More College of Design in downtown Franklin in 1967.

While the college and its design program have recently been acquired by another local university, the estate and its two historic homes at Franklin Grove will be restored for use as an event venue, art museum and gardens, entrepreneur incubator, and education center. The relocation of a Rosenwald school from Spring Hill, which was part of a nationwide program to educate rural African American children in the early 20th century, will enhance the educational offerings there, making it a multifaceted jewel in the middle of a thriving historic downtown and a testament to the influence of women in the education and preservation of our historic Franklin community.